The disturbing history of residential schools in Canada

Charlie Penahsewa, age 11, tuberculosis. Annie Howe, 7, also tuberculosis. Jane Warner, 10, cause of death unknown.

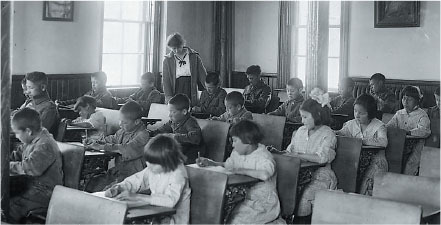

PHOTO: BRANDON INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL, BRANDON, MANITOBA, 1946

PHOTO: BRANDON INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL, BRANDON, MANITOBA, 1946

These are some of the children who died as students at Shingwauk Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie in the 1880s. Unlike many who died at residential schools, we know their names and where they were buried.

The disturbing story of Canada’s Indigenous residential schools has been brought back to national consciousness this year due to the confirmation of 215 unmarked graves at the site of the residential school in Kamloops. Reports of hundreds of confirmations of additional graves began to come in from other parts of the country. Undoubtedly more will be discovered.

The residential school system was run as a partnership between the federal government and several Church groups from the 1870s to the 1990s. The federal government provided the money and oversight while the churches established most of the schools and provided staff.

The schools were designed to isolate students from their parents and cultures so they would "acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men," as prime minister John A. Macdonald put it, as well as provide basic education. Many reserves lacked day schools, and legal changes between 1894 and 1920 made schooling compulsory.

In its investigation into the residential school system, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified 3,201 children who died while residential school students. Since that 2015 report close to a thousand additional deaths have been identified from records, bringing the known total to over 4,000. The true number may be 6,000 or more of the 150,000 students who attended.

For nearly a third of the deaths confirmed by the TRC, no names were even recorded by school officials – just numbers.

Between 1926 and 1950 the death rate of residential school students was between two and five times as high as that of other school-aged Canadian children.

Most often the deaths were from disease, especially tuberculosis, a common killer until the development of effective medicines in the mid-20th century, but also pneumonia, meningitis and other maladies. Diseases flourished in the schools due to crowding, poor facilities, inadequate nutrition and failure to keep sick students home or separated from healthy ones. Some students also died of accidents such as preventable school fires.

Perhaps the saddest stories are the six known suicides and the 33 or more students who died after running away from the schools to return to their parents or escape harsh treatment. In January 1937 Allen Patrick (age 9), Andrew Paul (8), Justa Maurice (8), and John Jack (7) ran away from the Lejac Residential School at Fraser Lake, B.C., after they were denied permission to visit their parents. All of them froze to death in the -29°C weather.

Schools often failed to inform parents their children were sick or had died. For nearly a third of the deaths confirmed by the TRC, no names were even recorded by school officials – just numbers. The government usually opposed returning bodies to the parents due to the expense involved. Instead, students were buried on or near school grounds, usually with wooden grave markers that have disintegrated over the years. Today their exact locations are often unknown – hence the use of techniques like ground-penetrating radar.

The TRC report attributes these horrors mainly to the federal government which forced students to live at the schools, but then chronically underfunded them and failed to set or enforce basic standards. These failures are inexcusable. It is astonishing how many people – parents and Indigenous leaders as well as several school, church and government officials – sounded the alarm for decades only to be ignored or resisted by bureaucrats in Ottawa.

The church groups who ran the schools are also to blame for designing, justifying and running a deeply broken system. And all of us, as Canadian citizens, and as Christians who share a faith with the perpetrators and many of the survivors, bear a responsibility to work toward a future in which every Indigenous child is cared for as God’s image bearer, known and precious to Him.

ARCHIVES OF CANADA

ARCHIVES OF CANADA

FOR FURTHER READING …

JOHN S. MILLOY, A NATIONAL CRIME: THE CANADIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SYSTEM, 1879 TO 1986, 2ND ED. (UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA PRESS, 2017)

Kevin Flatt is professor of history at Redeemer University in Ancaster, Ont. Read more at www.FaithToday.ca/HistoryLesson