The Church, First Nations and reconciliation

Listen to our podcast

First Nations children at Brandon Indian Residential School, Brandon, Man., in 1946. NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA / PHOTOTHÈQUE COLLECTION / LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA / PA-048571

"Rabbi, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me."

Once again Jesus is interrupted. It must happen to Him a dozen times or more. There He is, preaching some jaw-dropping piece of good news, and next thing the roof is coming apart, or a demoniac is shouting Him down, or a teacher of the Law is standing up to test Him, or Sadducees are lining up to trick Him, or Pharisees are cooking up a trap to ensnare Him.

But many people just want something from Him. Most who interrupt Him are simply preoccupied with their own stuff. They’re caught up with some earthy, urgent, agonizing matter that can’t wait for the sermon to end. They want answers to vexing questions, and they want them now. "Who is my neighbour?" "Good Teacher, how do I inherit eternal life?" "Son of David, have mercy on me – cleanse me, heal me, restore me!" "Lord, tell my sister to help me in the kitchen."

That’s the story in Luke. A man crashes into the middle of Jesus’ sermon with his urgent demand. "Rabbi, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me" (Luke 12:12). Well, that man does have a point. It’s hard to listen attentively to a sermon when your brother just bilked you out of your share of the family estate. A thing like that tends to consume all your energy.

A thing like that is powerfully distracting.

Many of my First Nations friends have difficulty listening to sermons. There are many reasons for this – some personal, some cultural, some historical – but much of it comes down to the issue of justice. They got bilked out of their share of the family estate. Land. Language. Children. A way of life. All and more were taken from First Peoples. And sometimes they itch to interrupt all our ethereal business about heaven and love and God and such with a burning request. "Jesus, tell my white brother to divide the inheritance with me."

Well, they do have a point.

But actually that’s not quite what First Nations people, at least the ones I talk with and listen to, are asking. Dividing the inheritance is not exactly their request, or not the things they ask first. Almost every First Nations person I know wants something else, something deeper. "Jesus, tell my white brother to reconcile with me."

I suggest this is worth interrupting our sermons.

And yet, is reconciliation even the right word? Many First Nations people don’t think so. Many observe reconciliation implies restoring the relationship to a former level of mutual warmth and trust and affection and intimacy. In most cases no such former relationship ever existed between Indigenous people and European settlers in Canada. In most cases our relationship has been marked by suspicion and distrust. In most cases we were never close.

What we need is a new story. A fresh beginning. A do-over. But to get to a new story, all of us must first become keenly aware of – and, I suggest, deeply troubled by – the story we actually have.

That was the hope that launched Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC was established to examine the history and legacy of Canada’s "Indian residential schools" and bring some closure and healing for those who suffered there.

The TRC was struck in 2008, launched in 2009 under the leadership of Justice Murray Sinclair, and wrapped up in 2015. The commission issued a seven-volume report which contained 94 Calls to Action. The work of the commission continues through the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation housed in the University of Manitoba.

In the seven years the TRC was active, the commissioners, along with many participants, heard the testimonies of more than 6,000 residential school survivors. These testimonies, taken together, are devastating, and yet strangely and profoundly inspiring. They narrate a long tale of abuse, neglect and evil, but also tell a story of resilience, courage and grace.

But note this: the TRC was initiated by First Nations people, featured the testimonies, almost exclusively, of First Nations people, and was attended mostly by First Nations people. It was the idea and work of First Nations people from start to finish. All with the aim of reconciliation. Not blame. Not restitution. Not score settling. But reconciliation – of getting the story straight so now, hopefully, we can begin a new story.

Non-Indigenous people in Canada should stand amazed and grateful and humbled by this. After all that’s happened, First Peoples still hold out a hand of friendship to us.

But many of us have just ignored it.

About 14 years ago, I started a small effort to get Christians to start caring about the Church’s relationship with First Peoples, and to inspire Christians to be at the forefront of creating a new story. I’ve talked to hundreds of people about it. I’ve spoken in dozens of churches on it. I’ve lectured at colleges and universities regarding it. I’ve been involved with several conferences dealing with it. I’ve written a number of articles focused on it. I have helped organize local initiatives around it.

One of these initiatives is even called New Story. It’s an all-day teaching event to help Christians understand the history and culture of Indigenous peoples, both nationally and locally, and what we as churches and individuals might do next.

I am seeing some things that give me hope. A growing number of churches, for instance, now open their Sunday services with an acknowledgement of the traditional lands on which they are situated. A few churches welcome, at least in small ways, some form of Indigenous worship in their Sunday gatherings.

More and more Christians are learning the beautiful and unique contributions First Peoples bring to the reading of Scripture. Genesis 1, for instance, depicts not humankind’s superiority over everything in creation, but our dependency on everything in it. Humans need air and water and light and fish and flocks and fruit to survive and flourish, and yet none of these things need us. Everything else in creation flourishes independent of our existence.

But I am also seeing in our churches many things that cause me distress. Continuing bigotry. Abysmal apathy. Deep contempt. Condescension. Resentment. Defensiveness. I would love to see all this change. And if you would too, here are a few things that can begin that change – a few steps toward a new story.

Learn the history

I am still astonished how few people in our churches know about the Doctrine of Discovery (the papal bull from 1493 upholding the divine right of Christians to take land from its "savage" inhabitants), Terra Nullius (the legal claim that "empty" territory belongs to the state that occupies it), the history of treaties, the history of colonialization, the history of the Indian Act, the history of Indian residential schools, and the current struggles and achievements of Indigenous peoples and communities in Canada.

And still fewer know anything about the local tribes and bands within driving distance of their church and home.

Why not strike up a church study group that, over the next few months, becomes well informed on all these things and then informs others?

Discuss the situation

There are many things the group might read and discuss, but I suggest you start with three things – Volume One of the TRC Final Report, the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which is underneath much of the TRC’s work and recommendations), and the 94 Calls to Action that emerged from the TRC. I suggest your group focuses on Calls 58 through 61, which specifically address the Church and its supporting educational institutions. (On a side note, I find it stunning Canada’s First Nations people issue 94 Calls to Action, but ask only four things from the Church.)

Make a strategy and take action

The next step might be to come up with a strategy for your entire church to respond to one or two of the Calls to Action. For example Call # 60:

We call upon leaders of the Church parties to the Settlement Agreement and all other faiths, in collaboration with Indigenous spiritual leaders, Survivors, schools of theology, seminaries, and other religious training centres, to develop and teach curriculum for all student clergy, and all clergy and staff who work in Aboriginal communities, on the need to respect Indigenous spirituality in its own right, the history and legacy of residential schools and the roles of the Church parties in that system, the history and legacy of religious conflict in Aboriginal families and communities, and the responsibility that churches have to mitigate such conflicts and prevent spiritual violence.

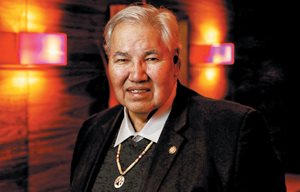

Justice Murray Sinclair, now a senator, was chief commissioner of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). PHOTO: WINNIPEG FREE PRESS / PATRICK DOYLE

One local church I know gathered a group of about ten people who spent several months discussing how their church might respond to this one Call to Action. That led to an evening where the group hosted a Blanket Exercise (www.KairosBlanketExercise.org) for the entire congregation. They also invited several elders from the nearby First Nations community.

This one initiative broadened the conversation, and soon several members of the church were meeting regularly with some of the elders to discuss ways they might work together. That led to several youth from both communities meeting every week, sometimes at the church, sometimes at the community.

That led to real friendships and that led to transformation.

What might your local church do?

Real friendship

That last story brings us to the most important thing – real friendship. It still surprises me how few people in our churches have even one Aboriginal friend.

That was me a few years back. Indeed it was me for most of my life. Until about 15 years ago, I didn’t even know a First Nations person.

Then I became good friends with one First Nations man. That opened the way for other friendships. And the more First Nations people I got to know, and the more I learned their stories and came to know their hearts, the richer I became. My First Nations friends are funny and kind and generous and wise. And they are hurt and sad and wary and angry. But they still want to be my friend.

I have gained and grown much from these friendships. I discovered I need my First Nations friends more than they need me. I need my friends to be my teachers and examples and guides. I need them to show me how to live out my faith more fully and authentically – to pray with deeper faith, to share with greater joy, to stand up more bravely under trial. I have learned from them what it means to forgive from the heart. And I have learned from them the true meaning of resilience.

Every new story is rooted in friendship and leads to deeper friendship. That’s where the real transformation happens.

Canada’s TRC, intended to address the history and legacy of RSs, followed the pattern set by other country’s TRCs, such as the one in South Africa. The South African TRC was intended to address the history and legacy of Apartheid. But there is a significant difference between Canada’s TRC and those of other countries. In South Africa, as in other countries, the TRC was tribunal in nature. That meant that it included the testimonies of over 2000 perpetrators – those who engineered and carried out the policies of Apartheid, those who benefitted from it, but especially those who enforced it, often by brutal and illegal means: police, for instance, who committed extra-judicial murders to silence political dissent.

In Canada, for various reasons, the TRC was non-tribunal. In practice this meant that it heard virtually no testimony from anyone who "ran the system": no government agent who scooped a six-yearold from her home and dragged her away from her wailing mother, no priest who summoned a 12-yearold boy to his study and sexually abused him, no nun who broke a little girl’s neck throwing her down the stairs, no teacher who publicly mocked and humiliated a student for peeing his bed, no school administrator who saw all this and turned a blind eye.

None of them said a word.

Which is a problem. Because – well, think about it. What if you suffered deep harm at the hands of another person, told your story publicly, and all the while the person who harmed you seemed neither to notice or care, and just stayed silent?

It would, at the very least, be hard after that to reconcile with that person. And it would be hard to reconcile with anyone associated with the system in which that person operated. It would be hard to begin a new story. Which is why this all comes down to you and me. Will I too stay silent? Will you?

Let us begin.

Mark Buchanan is an author and associate professor of pastoral theology at Ambrose Seminary in Calgary, Alta.