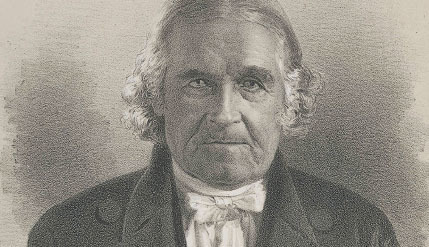

Baptist pioneer Edward Manning

Like other frontier societies, Nova Scotia in the late 18th century was a place of rapid change with few stable institutions and patterns of life.

This was equally true of the spiritual life of the colony. While many of the settlers had brought religious convictions with them from the American colonies or Britain, at first there were few churches and few pastors. Travelling preachers and evangelists, most famously Henry Alline (1748–84), later called the "apostle of Nova Scotia," had a huge impact, inspiring renewed devotion, changing theological allegiances and provoking controversy.

In this context, Edward Manning arrived in the colony from Ireland as a three- or four-year-old in 1769/70 with his parents Peter and Rebecca. When he was 10 years old, his father murdered someone and was hanged.

As a teenager Edward seemed to take after his father. He led what he later admitted was a "riotous" life of rebellion against the standards of God and society. Tall and brawny (at 6′4″, very tall by the standards of the day), he was described by a contemporary as a "man of great courage and muscular force." At 16 he and a friend unexpectedly ran into three bears in the woods. They escaped the potentially deadly encounter because Manning killed all three with nothing more than a hatchet.

A change began when Manning heard the great evangelist Alline preach, imploring him with tears in his eyes to accept Jesus. Although he resisted at first, in 1789 he converted at age 23, joined a church in Cornwallis and soon began preaching himself.

ENGRAVING: THE ESTHER CLARK WRIGHT ARCHIVES / ACADIA UNIVERSITY, USED WITH PERMISSION

ENGRAVING: THE ESTHER CLARK WRIGHT ARCHIVES / ACADIA UNIVERSITY, USED WITH PERMISSION

16: PERCENTAGE OF NOVA SCOTIAN POPULATION THAT WAS BAPTIST IN THE 1827 CENSUS

GEORGE A. RAWLYK, RAVISHED BY THE SPIRIT: RELIGIOUS REVIVALS, BAPTISTS, AND HENRY ALLINE, MCGILL-QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1984.

These were wild times that fit Manning’s wild streak. Together with a group of other young men, he became a central figure in an extreme movement called the New Dispensation. It taught that believers, because of their direct relationship with God, no longer needed to follow moral rules or church teachings, or even rely on the Bible. They disrupted services and split churches, preaching whatever (they believed) the Spirit led them to preach – no Bible needed.

As had happened before and since in church history, people began to do bizarre and disturbing things under the influence of such ideas. Manning had enough second thoughts that he left the movement in 1792.

Tragically, an incident in 1805 in neighbouring New Brunswick showed just how dangerous the New Dispensation could be. Encouraged by its teachings, a young woman named Sarah Babcock had claimed to be a prophetess and began predicting the Lord would soon return. This message triggered something sinister in her father Amasa. One day he ran through the snow barefoot shouting, "The world is coming to an end!" and when he re-entered the house, he assembled his family and ordered his sister Mercy and brother Jonathan to strip naked – while he sharpened a long knife. Shouting, "The Cross of Christ!" he suddenly and fatally stabbed Mercy. Fortunately the rest of the family came to their senses, escaped, and with the help of neighbours were able to subdue Amasa. He too was hanged for murder.

According to historian George Rawlyk, the incident helped convince Manning he had been right to turn from such "great irregularities." He became a stable pastor of a local church, adopted a carefully worked out system of doctrine (Baptist Calvinism) and promoted sound church organization. Manning strongly agreed with a friend who wrote to him that "Zeal is very useful … but it should be accompanied with wisdom lest it should do, as it has often done, much harm."

Manning was instrumental in setting up an association of pastors and churches that could hold each other accountable, which developed into the main Baptist denomination in the region. He founded Horton Academy, a school for boys in Wolfville, in 1830, and led the drive to start a college which eventually became Acadia University. He successfully challenged unjust laws that limited licenses to perform marriages to only Anglican clergy. He even convinced Nova Scotia Baptists to sponsor their first overseas missionary (Richard E. Burpee), who went to Burma in 1845.

He faced challenges too – poor health for him and his wife, the death of two of his daughters and a congregation that failed to pay him a regular salary. But he devoted the rest of his life to adding wisdom to zeal, and helped lay the foundation for a Maritime evangelicalism that possessed both.

Kevin Flatt is associate professor of history and director of research at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ont. Read more at www.FaithToday.ca/HistoryLesson.