Manitoba writer Dorene Meyer reflects on what she’s been learning from her mother’s work as a foster parent of Indigenous children in the 1960s

In the mid-1900s many Indigenous children in Canada were forcibly removed from their families and communities, and placed into non-Indigenous families, including my own in Sioux Lookout, Ont. Many of these children were never reunited with their biological families or returned to their home communities.

Known as the Sixties Scoop, these tumultuous events occurred when children’s aid societies were just beginning to be organized in some larger centres. Most of the reservations were remote and only accessible by air. There was a huge language and cultural barrier between the families of the children and the social workers apprehending the children.

Today it seems impossible to imagine this could have been permitted, but these were Indigenous parents and grandparents who had attended residential schools and been taught to fear the non-Indigenous authorities. Indigenous people were not even allowed to vote until 1960. They had to have permission from the Indian Agent (a representative of the federal government) to leave their reservation.

Indigenous people could not own homes or businesses. The Hudson’s Bay Company owned the only store on the reservation. Indigenous people had previously lived by fishing, hunting, gathering and trading, but this had involved travelling south in the winter and north in the summer, something they were no longer permitted to do. Living off handouts from the government is no one’s choice way of living, but that was the reality for many Indigenous people living on federally allocated reservations.

My mother’s notebook

There are no truly accurate records of the numbers of Indigenous children taken from their homes and communities during this era. But I have a copy of one of the records. It is a spiral-bound notebook where my mother recorded the child’s name, Indian band number and the number of days she took care of that child in her home.

These are the only records that exist, and I have kept this notebook all these years (earliest recorded date was March 1963) in case any of these children might ever need or want this information. This was decades before the computer age. Many official records were handwritten and often these records were destroyed when the buildings that housed them burned down.

In most cases my mother was paid by Indian Affairs, but as the federal government gradually transitioned the responsibility for child welfare to the provinces, my mother was paid by the township and then later by a children’s aid society. Her notebooks suggest she got paid $3.50 per child per day.

My mother has passed on. I have no way of judging her motives, but I believe she genuinely felt she was rescuing and offering protection to children in dire need. I don’t believe she cared for the children because of the money.

Some children came to our home not because of perceived abuse or neglect, but to receive medical care unavailable in isolated northern reserves. These children might then stay for years or even become permanent wards of the court (also called Crown wards) if they needed ongoing treatment.

No provision was ever made for them to visit their families or for their families to visit them. Airfare to remote communities was prohibitive. Even now, you can fly from Winnipeg to Toronto cheaper than you can fly from Winnipeg to most First Nations communities, and there are still a lot of fly-in communities where there is no road access.

When a child became a ward of the court, they automatically became available for adoption. Newspapers published advertisements and articles about the need for adoptive parents. One in the Jan. 27, 1979 edition of The Citizen appealed for Ottawa "parents with enough time, energy and love for four lovely lively children," earlier described in the article as "all loveable, all good-looking … all average or better in intelligence." Each child was then individually described and there was a photo attached. People enquiring about adopting the children were given only one directive. "In your letter tell something of your present family and your way of life."

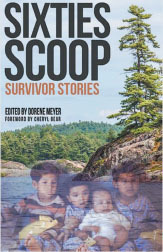

A photo taken in the 1970s by Dorene’s mother of the foster children in her care at the time. PHOTO: COURTESY OF DORENE MEYER

Past prejudices

During the Sixties Scoop era, most non-Indigenous Canadians thought their homes and families were superior to those of Indigenous people. It is true most non-Indigenous families were wealthier in economic terms. But of course we know children need more than just their physical needs met.

Children can continue to exist, but can’t thrive unless their emotional, mental and spiritual needs are also met. Children can be ripped away from their family, community, language, culture and everything familiar they have ever known, and still physically survive. But the resulting trauma can have devastating and lifelong consequences.

The children who came to my mother’s house were quickly bathed and deloused with coal oil (the treatment of that day), and dressed from a selection of used clothing. Their own clothing they arrived with was usually thrown away. The children were required to call my mother "Mommy." Only a couple of Indigenous language words were used occasionally in the beginning – the word for eat and the word for no. Nothing familiar to hold on to – no mementos to touch or smell or see – remained for the children who lived in our house.

In the media of that day (The Daily Bulletin, circa 1972), my mother was lauded as someone who takes in "the homeless and uncared for, who above everything else need the warmth and love of a real home, and running that home, an understanding mother."

Those were the days when children were seen and not heard, and that was true in the home I grew up in as well. Children were packed into beds like sardines. If you wet the bed, you were spanked, and in my mother’s case, with a leather belt. Children ate what was in front of them or they didn’t eat at all.

There were no choices given to any child. Meals, chores, outdoor time, bath-time and bedtime were all closely regulated – how else to manage between 20 and 25 children at any given time? There were few conveniences back then (no disposable diapers) and my mother worked from early in the morning until late at night.

Losses and adoptions

All the older children helped with the younger ones. We took on surrogate parenting roles of bathing, dressing, feeding, changing diapers, walking kids to school and reading bedtime stories.

This may be a familiar scenario to others from large families – except these younger brothers and sisters, cuddled and loved one moment, would vanish without any warning from our lives forever. Perhaps my mother was told where the children went – on to other foster or adoptive homes, or rarely back to their home communities – but for us, they were simply gone.

My mother took care of several hundred children, but there are only three I have been able to keep in touch with.

I feel I have no right to mention my own pain or sense of loss. My pain is nothing compared to the loss experienced by the biological families of these children and by the children themselves. But there is a deep-abiding sadness in my heart that never really goes away.

I know my childhood experiences have made me overprotective of my own children and grandchildren. I’ve had recurring nightmares all my life of children being lost. In my dreams I try to find them, but I can’t. They remain out of reach, always lost to me.

My mother adopted some of the children, again with the firm belief she could provide better care for them than what their birth parents could. I have a copy of the letter my adoptive brother’s mother signed. It reads, " … agree to give custody of [child’s name] to [my mother’s name] in order that the child can be provided with proper food and clothing, and a comfortable home."

There was no thought given at that time that the child’s extended family or community could provide care. It was just not even considered.

Toward healing

Recently I edited a book about the Sixties Scoop, and it was one of the hardest things I have ever done.

For so many years I pushed down the memories of my childhood, afraid to confront the source of my night terrors and daytime depressions. A breakthrough began 20 years ago when I helped organize and then sat in on a conference from Rising Above (www.RisingAbove.ca), an Indigenous ministry that offers counselling to those dealing with childhood trauma. Their motto is "First Peoples helping First Peoples," but their words also touched my heart. My healing journey began and I am so grateful.

Writing was an integral part of my healing. I produced a series of fiction and self-help books that were as much for me as my readers. As the years passed I took every opportunity to also help others tell their stories by writing profiles, editing memoirs and creating anthologies. My focus has been mostly on Indigenous writers.

I’m not trying to make up for what my family did. I can’t. There is no amount of writing or apologies or compensations that can make up for a childhood lost. But to do nothing is not acceptable either. And as hard as it was to edit Sixties Scoop Survivor Stories – and especially writing about my family’s involvement as a chapter in the book – it felt as if it was the very least I could do. I will continue to tell the story.