And what we can do about it

Listen to our podcast

En français

Some time ago I was invited, with a colleague of mine, to participate in a public debate as the opening act of an atheist convention. There would be a few hundred atheists from around North America and even a few from overseas. We were to be paired with two of their members and, in a strange sort of way, I felt honoured to be asked. We readily accepted and began preparing.

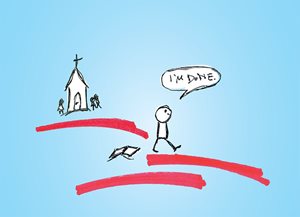

At the conference it became obvious most people there were not merely atheists, but also former members of some religious group from which they had been "set free." They were now celebrating their new liberated status as atheists. The theme of the conference was Imagine No Religion. One of the debaters we engaged was a former Southern Baptist who had been preparing for ministry, the other had been a Catholic altar boy. There were former Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons, Muslims and the like among the attendees.

This event is one example among many that something different is happening in the world of faith and religion. There is a new and passionate kind of skeptic out there, one who in the past was a devout, worshipping member of a faith community. Some have even been leaders in the Christian community, pastors, professors, theologians, authors, church planters and theology students.

This exodus of people from the Christian community is being supported by a growing number of organizations, usually internet-based, devoted to assisting and encouraging them in their journey away from faith. One example is the Clergy Project, an organization established in 2011 "to provide a safe haven of protected, anonymous online community for former and active religious professionals who no longer hold to supernatural beliefs" (www.ClergyProject.org). Another is called Christians Anonymous, "a resource for recovering Christians."

Perhaps you’ve met skeptics like this. If so, you will know their take on Christianity is different from other skeptics who may never have been an active part of a church. Your conversations with them will not be the same. People like these do not need to be told what it’s like to be a Christian because they were once on the inside themselves. They were there praying and worshipping like any other Christian.

In some cases they know their Bible, theology and history of Christianity better than the average Christian. The way they formulate their objections against Christianity often involves different argumentative strategies than the ones they know most Christians are prepared for, and they are well aware of the typical replies Christians are likely to give (since they once used the same responses themselves). Furthermore, they are often granted special credibility in our culture because, unlike most other critics, they were once part of the group they are now critiquing.

What kind of Christians walk away from the faith?

Perhaps you’ve wondered how anyone could walk away from Christian faith. Did they truly know the God who became one of us so we could be reconciled to Him and each other? How can anyone walk away from that?

Actually there is really nothing new about this phenomenon. Even Paul wrote in the New Testament about two men Hymanaeus and Alexander, who in his words had "suffered shipwreck with regard to the faith" (1 Timothy 1:20).

The more you read such contemporary stories, the more difficult it becomes to establish tidy categories for people who leave the faith. Some speak of a traumatic negative experience they had, or a series of them. For others it was being let down by members of the Christian community. In certain cases there was a moral failure coupled with difficulty finding renewed acceptance among former Christian friends and colleagues. Still others speak of unresolved puzzling questions around certain Christian teachings that ate away at their confidence in the truth of Christianity.

The list of possibilities here is long and includes such issues as the presence of textual variants in biblical manuscripts, discrepancies among the synoptic gospels, harsh actions of the God of the Old Testament, biblical sexual morality, miracle claims, biblical statements concerning the origins of the earth, and the alleged incoherence of the concept of God, to name a few.

When you look at the journeys of these former Christian leaders, you see a variety of causes and motivating factors, and usually a combination of them.

Matt Dillahunty, in his words, was raised in a loving Southern Baptist home. As a young man he set out to reaffirm his faith with a plan to attend theological seminary and prepare for ministry. But after investigating a series of topics he claims his faith was weakened and eventually destroyed. As he puts it, his study of philosophy, science and other academic disciplines helped "free" his "mind from the shackles of religion." He now leads the atheist community in Austin, Texas, as an articulate spokesperson for his views. He is prominent at public gatherings of atheists throughout North America and also on various internet sites.

As a young man John Loftus began to read the Bible uncritically, as he puts it now. It all seemed so real to him and eventually his "life was radically changed." He began looking for opportunities to tell people about Jesus, even going out hitchhiking with the goal of witnessing to anyone who picked him up. My guess is he put most Christians to shame in terms of his passion and service for Jesus. He went on to earn MA, MDiv and ThM degrees from evangelical schools. He later studied philosophy at the PhD level and currently teaches philosophy.

Today he sings a different tune. He has written a thick and well-endorsed book (Why I Became an Atheist, Prometheus Books, 2008) outlining his journey to atheism and setting out his reasons for rejecting the faith. He also maintains a blog devoted to "debunking Christianity," and has developed a team of bloggers. Claiming to be "living life to the hilt," he states his wish that everyone who reads his writings could experience the freedom he has found.

Bart Ehrman is currently chair of the department of religious studies at a well-known American university. As a devoted Christian, he attended both a prominent Bible college and a highly regarded Christian college in his younger years, but eventually rejected the faith. During his years as a graduate student, Ehrman encountered difficulties with the biblical text which were never satisfactorily resolved. In time his confidence in the Bible evaporated and eventually his faith came crashing down.

We can probably all name people we care about who fit this profile of someone who once believed and now considers themselves an atheist.

Is productive engagement possible?

How can we best engage someone who has turned from the faith? We should begin by praying for those who find it in their hearts to walk away. Let’s always remember they are not the enemy. God does not love them any less, nor should we. We can befriend them and even engage them.

Second, somewhere in our discussion it’s helpful to ask the most basic question of all, namely what exactly were they rejecting when they walked away? Then we must encourage them to share their stories fully while we restrain our natural impulses to interrupt and correct. Spoiler alert – this will not necessarily be easy listening. Their responses may be personal, emotional or intellectual, but there is nothing to be gained by avoiding the issues. Our number one task at this point is to listen.

Third, let’s surprise these folks with our grace and love. I say surprise because we, as Christians, simply do not have the best record here, whether in dealings with our own brothers and sisters, or those on the outside. In some cases, as noted earlier, it was precisely a perceived lack of love and acceptance in a low time that contributed to their departure.

Chris, a student of mine, spends substantial time interacting with Mormon missionaries. He commented recently their experience with evangelical Christians is being treated with unfriendliness, even hostility, day after day. By the time they near the end of their two-year stint, most view Evangelicals as hostile people.

As Chris put it, if Christians would simply love those Mormon missionaries, it would make it easier for people like him to have productive conversations with them later. I have received the identical comment in my own interaction with young Mormon missionaries.

The antidote here is crystal clear, whether in dealing with our own brothers and sisters or those on the outside – "Love your neighbours as yourself" and "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you."

Fourth, let’s get prepared to enter meaningful dialogue with our brothers and sisters who have turned away. We can all advance one or two steps in our understanding of the journeys and stated reasons they give for leaving. Some among us, of course, can go further and study these issues deeply to provide much-needed assistance to the Christian community. The Apostle Peter calls us to "always be prepared to give a reason," but now this comes with an added urgency. We do it not simply to share the faith, but to keep it too.

Fifth, those who preach to our congregations week by week must consistently draw a distinction between the infallible text from which they preach and their own interpretation of it. Theologian J. I. Packer once told his students that while he believed in an infallible text, he in no way believed in an infallible human interpretation. We need to encourage those who hear our preaching to examine and question our teachings just as the Berean Christians in Acts 17 were commended for doing with the Apostle Paul.

Christian culture should be a culture of thinking and questioning. When this happened in Berea, the result was others coming to faith.

This is especially important in our handling of secondary nonessential Christian teachings where there is legitimate disagreement among Christian scholars who hold a high view of the Bible. It is legitimate to develop and hold settled views on these secondary matters, but if we preach our views on these matters with the same level of certainty as we give to essential historic Christian doctrines, we may unwittingly send the message that being a Christian requires a commitment to essential historic teachings and also to our own particular views on the secondary matters as well.

By implication we will have placed them on the same level. This can have a devastating effect on thinking, questioning people in our churches who may find evidence for a different point of view on a secondary matter. It can put them in the untenable position of having to decide between setting aside their questions or, tragically, feeling forced to turn from the faith altogether.

The Bible and the Christian tradition have a long history of encouraging us to think and reason, and not to believe ideas that fly in the face of evidence. Amazingly Christianity is willing to stake its entire message on a historical moment – Jesus’ resurrection from the dead – and then invite the world to investigate whether it really happened. If it did not, even St. Paul writes that the Christian message is a false hope and we should walk away (1 Corinthians 15).

Finally, we should not lose hope when considering people who have turned from the faith. As my former professor John Woodbridge, renowned Christian historian and himself a former atheist, reminds us in a February 2018 article in ChristianityToday.com, we need to "countermand the widespread secular myth that atheism is the inevitable final intellectual stop for any serious, educated person."

Woodbridge points out the list of Christian scholars who once were atheists is long and impressive. It includes C. S. Lewis, John Warwick Montgomery (apologist and church historian), Kenneth S. Kantzer (theologian and editor of Christianity Today), Carl F. H. Henry (theologian and editor of Christianity Today) and Alister McGrath (scientist and theologian).

Woodbridge also notes these thinkers, and many others, moved from disbelief to faith not in spite of their intellectual study, but as a result of it. And their work can provide valuable apologetic insights into some of the difficult questions they were forced to navigate in coming to faith.

Listen to our interview with Paul Chamberlain at www.TheEFC.ca/Podcasts.

Paul Chamberlain is director of the Institute of Christian Apologetics at Trinity Western University in Langley, B.C., and professor of apologetics, culture & Christianity, ethics and philosophy of religion. His latest book is Why People Stop Believing (Cascade/Wipf & Stock, 2018).

FT ON THE GO

We think this article would be great to discuss with your small group or Bible study. We encourage you to make copies and share a brief discussion using these questions. To share electronically just point group members to www.FaithToday.ca/WhyPeopleStopBelieving. Let us know how it goes!

- Have you been surprised by Christians who have walked away from the faith?

- Paul Chamberlain suggests we surprise those friends with our grace and love. How do you respond to that suggestion?

- How can churches do a better job encouraging questioning and the sharing of honest doubts in faith?