IN A CULTURE OF GREED, ARE OUR DESIRES ALWAYS WRONG?

PHOTO BY MYLES TAN

Listen to our podcast

I had a thousand reasons for mistrusting my own desires, many rooted in my prodigal story. For despite having parents who faithfully took me to church on Sunday mornings, Sunday evenings, even Wednesday nights for all-church dinners and prayer meetings, I led a wild early adolescence so terribly cliché as to be uninteresting. At the time I didn’t abandon belief in Jesus so much as put it off. Save it, as it were, for the more settled years of adulthood. I wasn’t not a Christian, I told my boyfriend at the time, who had also been raised by Christian parents. But he was less convinced than I was about our orthodoxy.

If my teenage rebellion was unimaginative, my conversion was equally ordinary. At 16, I was the girl whose heart broke into a thousand repentant pieces when a summer camp speaker pleaded for us to surrender all. What do you want? Where are you headed? Will you follow? These are the questions the resurrected Christ put to me, and I answered them in the only way possible when the Damascus light both blinds and illuminates.

More than 25 years later I continue to marvel that life can change as immediately and irrevocably as mine and Saul’s. At school they started calling me "Church Lady," a nickname warranted by my scandalous decision to stop sleeping with my boyfriend. At the time however I lacked confidence in God’s grace. Could I make permanent my repentance? Picturing conversion as the precarious act of taking hold of God’s hand, I feared without proper vigilance I might lose my grip.

The prophet Jeremiah describes the human heart as "deceitful above all things, and desperately sick" (17:9). For prodigals like me this is no ancient adage. We are suspicious of desire because we drank the bitter dregs of our own depravity. The only reasonable conclusion we are left to draw is that human desire is the snake that can never be charmed. We can’t trust ourselves to want.

OBLIGATIONS OF LOVE

I stand in line to pay for my groceries, praying for the frazzled young mother in front of me whose toddler refuses, upon being asked for the 53rd time, to sit down in the cart. She fumbles with her credit card and leans toward him, whispering in his ear. Perhaps she barters for co-operation. Perhaps she warns of pending consequences. All I know is that her whispering falls upon stubborn, deaf ears and her face darkens. I see the thread of her patience pull taut, and I pray harder for his compliance. I will him to make this easier.

Now that my children are school aged, I go to the grocery store alone. And I won’t lie. Pushing the cart at leisure is a greedy pleasure, freedom hard won from the early frantic years of parenting five young children. If, after my conversion, I had feared falling prey to my own lusty will, in my life as a young mother desire became a luxury impossible to indulge. Most mornings I was lucky to brush my teeth.

Taking care of young children, an ailing parent or an infirm spouse is necessarily a daily act of kenosis, obliging us to the self-emptying of Jesus Christ Paul describes in Philippians 2:7–8: "He made Himself nothing, taking the form of a servant… [and] humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross."

In fact love in all its most practical forms requires breaking and spilling out our lives for the sake of others. What room can be made for desire (if we mean self-will) when our lives are constrained by our commitments of friendship, parenting, marriage and ministry? When we are needed by others?

If, as Martin Luther insisted, we are homo incurvatus in se – people curved in on themselves – doesn’t entertaining our own desires move us further from our obligations to love, to give, to serve and self-sacrifice?

We shouldn’t be troubled to want.

GOD’S GREAT AMBITION

Several years ago I was reviewing a book for another publication and startled at the author’s wrong-headed advice about discerning the will of God. He warned readers about the dangers of human desire and his advice was simple: "Write out all the things that you have wanted from life. Finally, draw a cross over it as a symbol that you are offering it in sacrifice to God, saying, ‘Not my will, but yours be done.’"

Years ago I would have formulated it exactly as that particular author did. You are a selfish and greedy being, and your desires promise to catapult you over the proverbial cliff. If you want to be faithful, you must rid yourself of the contaminant called desire. This was my practical theology of desire meant for safeguarding myself from myself.

But I don’t think of desire in the ways I used to.

The change began with discovering God was far more ambitious than I ever gave Him credit for, that He wasn’t in the business of gussying up, but making new. That is to say that God is committed to the believer’s total rehabilitation – of behaviour, of belief, of desire.

Moreover, as Philippians 1:6 promised, He would be overseeing that work when I could not or would not. In other words, my self-mistrust was not the noble attempt at holiness I had once believed it to be. It was a spectacular failure to apprehend the most fundamental truths of the gospel – that it is by gracewe are being saved.

SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

St. Augustine, the 4th-century bishop and church father, had a prodigal story familiar to many moderns. Though he had been raised by a Christian mother, in his adolescence and early adulthood Augustine dabbled in mystical philosophies, pursued crass professional ambition and indulged sexual lust. He fathered a child out of wedlock, and when the longstanding relationship with the child’s mother eventually ended (class difference would prevent the two from ever marrying), he pursued other illicit sexual relationships.

After a period of intellectual questioning and spiritual searching, Augustine resolved that the Christian gospel was true. But he was prevented from following Christ, admitting his lusts held him back. "I had discovered the good pearl," he writes in The Confessions. "To buy it, I had to sell all that I had; and I hesitated.

"My old loves held me back," Augustine describes. "They tugged at the garment of my flesh and whispered, ‘Are you getting rid of us?’"

Despite wanting to surrender himself to Christ, for a period of time Augustine despaired of his own conversion, necessarily predicated, he thought, on his own ability to turn from his disordered desires. But God sent him a vision of Lady Continence, a woman surrounded by throngs of Christians, young and old.

In the vision she stretched out her hands to Augustine and asked him, "Are you incapable of doing what these men and women have done? … Cast yourself upon [Christ], do not be afraid. He will not withdraw Himself so that you fall. Make the leap without anxiety; He will catch you and heal you."

Then, in the more well-known part of his story, Augustine wandered into a garden and heard a voice imploring him to pick up and read, pick up and read. Happening upon a copy of the Scriptures, and at seeming random, he opened to the book of Romans, his eye falling upon 13:14: "But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh to gratify its desires."

At that moment Augustine fell into the arms of Christ, believing those arms strong enough, safe enough, for him and his irrepressible lusts.

He discovered that caught in the arms of Christ, no one falls.

THE TASK OF DISCIPLESHIP

In his important book Desiring the Kingdom (Baker, 2011) and its laymen’s companion You Are What You Love (Baker, 2016), James K. A. Smith, professor of philosophy at Calvin College, argues we have been duped by Enlightenment thinkers like Descartes.

Smith says such thinkers have wrongly taught us that human beings are primarily thinking creatures governed by their rationality. As anyone knows who has recently visited the dentist and been lectured on the benefits of flossing, we can understand what’s right and still fail to do it.

As Smith argues we aren’t pushed by belief so much as pulled by our loves – lured and seduced more than informed and persuaded. In other words, it is not thinking that steers the man, but desiring.

Desire, as an integral dimension of what it means to be human (and made in the image of a desiring God), can’t be abandoned, even though we sense its cunning and near reflexive corruption. It must be tamed and trained, which makes the task of discipleship not so much the job of helping people believe differently so much as want differently. The formation of holy desire must be the impulse of our individual and corporate spiritual practices.

Smith’s book helped me interrogate some of my mistaken assumptions about desire, even holiness. Was desire always wrong? Would obedience always lead counter to desire? Or could human desire, rescued and reformed by the indwelling Spirit of Christ, be a wellspring of good?

In other words, was the measure of holiness its inherent friction – doing what we least wanted? Or was the truest test of holiness the degree to which our will was conformed to God – that we learned to want as He did?

THE CALL OF DESIRE

Perhaps it will seem like my journey toward better understanding desire was a purely theoretical exercise, informed by books like The Confessionsand Desiring the Kingdom. This would be false. I stopped championing the abandonment of desire because eventually it proved unworkable.

First of all, though I might not have been able to trust myself to want, I couldn’t pray without wanting. Certainly I could imitate the feeble, halfhearted prayers I seemed to hear huddled up in small groups, even thundered from pulpits – prayers that stopped short of real desire to prevent risking any real disappointment.

I could make "your will be done" the safe tagline to all my prayers, using those words not as a means to surrender so much as avoidance of self-scrutiny and self-disclosure.

I could keep the pretense of praying without ever really investing myself in the radical propositions Scripture puts to us – that there is a good God who inclines His ear to the pleas of His people, who is poised to do good in the world and for whom nothing is impossible.

Sure, I could pray without wanting. But if I wanted to pray like Abraham and Hannah, boldly pleading for my Sodom and Samuel, I would need desire – however unruly, myopic and self-serving.

And I would have to trust in the God who heard the unvarnished prayers of the psalmists, leading them beyond their blind rage and grief and irreverent accusation to places of praise. To be sure, God didn’t owe me answers to my prayers as I often wanted to dictate them, but without those prayers what intimacy with God was really possible?

I began to see long-term change was impossible apart from changed desire. I had my fair share of failed resolutions, promising to get in shape, to send birthday cards more regularly, to read poetry and practise Sabbath. But these were only obligations to which I assented on an intellectual level, things I knew would be good for me. My commitment was buoyed for a period of time – but never long enough.

As the years cluttered with stillborn intentions, I found I needed a conversion much deeper than a change in belief. I needed new desires. And for that I needed the grace of the God who worked in me, "both to will and work for His good pleasure" (Philippians 2:13).

This began to change the way I approached the painful places of much-needed transformation in my life. Whereas before I might have tried muscling the do-gooding required by God, now my first efforts (instead of my last) were aimed at confession, surrender and pleas for help. God, I don’t even want what you want. Give me a heart that delights to do your will!

I began to see this is the model of holiness we see in Jesus – not desire-less obedience, but desire-full. That in the Garden of Gethsemane Jesus did not abandon desire so much as lay it down. That the cross was not His sanctimonious grinning-and-bearing it for God, but His fullhearted delight: "Behold, I have come to do your will, O God" (Hebrews 10:7).

And finally I began to understand desire was required not just for praying and personal transformation but for participation in God’s mission.

For years, I thought of God’s calling as synonymous with suffering, that whatever I least wanted to do was the very thing God required. Calling was obedience in the abstract, and it required the denial of any kind of attention to my unique gifts, opportunities and longings.

But this led to volunteering haphazardly, following need wherever it led. Slowly I began to wonder if the desires I had for seeing God’s Kingdom coming were meant to be followed.

What if, as one example, the desire to write a book wasn’t a rogue impulse to deny, but a signpost to follow? What if desire, on this side of conversion, had not just the possibility of derailing us into selfish pursuits, but could enroll us in Kingdom work?

I learned holy desire was a match to strike – and prayer, transformation and mission were fires to light.

YOUR KINGDOM COME

It was years-long meditation on the Lord’s Prayer that gave final shape to the idea that desire, in the life of the Christian, had potential for good. The prayer Jesus taught His disciples to pray serves as a kind of script for holy longing, for a world where God is rightfully given His due, where the curse is reversed and humanity flourishes, where reconciliation is possible, even a world where we are protected from our own betrayals.

The Lord’s Prayer proposes a way of being in a world governed by a good Father – even a way of desiring well from Him. It is both a caution and call to desire.

"The whole of the good Christian is a holy longing," wrote St. Augustine in a sermon on 1 John 4:6. In other words, desire is not just a rope from which we hang ourselves. It can be the thread we follow out of our own darkness – and into Everlasting Light.

Our Father, who art in heaven. Teach us to want.

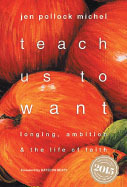

Jen Pollock Michel is the author of Teach Us to Want(InterVarsity, 2014). She offers a free six-week Bible study on desire at www.JenPollockMichel.com. Her second book Keeping Place: Reflections on the Meaning of Home will be released by InterVarsity this spring. She lives in Toronto with her family.