How saying goodbye has changed and why it matters. An essay by Tim Perry

Listen to our podcast

→En français

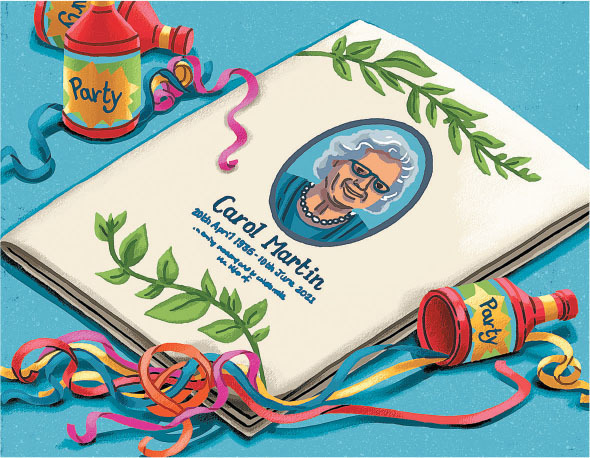

Illustrations by Eva Bee

"Today the remains of the real Margaret Hilda Thatcher are here at her funeral service. Lying here, she is one of us, subject to the common destiny of all human beings." So began the funeral sermon for Margaret Thatcher, the first woman to serve as prime minister of the U.K., a controversial figure in both life and death. But Bishop Richard Chartres, her funeral preacher, set all that aside with a simple sentence. On that day Margaret Hilda was subject to the destiny of us all.

Many of us watched some or all of Prince Philip’s funeral in April 2021 – no eulogy, no sermon, no lionizing of the dead. Except for his medals on the altar and the recitation of titles, it was a plain Christian funeral with readings and hymns appropriate for a naval officer. In his medals and titles, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, may well have been present, but at his deliberate design this was a service about God.

What is true in each of these instances is, finally, true for every human being. My uncle used to sing a song that captured the sentiment more plainly, but no less vividly – "Six Feet of Earth Make Us All One Size."

The death rate for human beings remains constant at 100 per cent.

I sometimes wonder if Christians are in the process of forgetting this. In my work as a pastor, an assistant to a funeral director and on-call clergy for a local funeral home, I have seen far too many believers’ funerals that look and sound like a retirement roast where the guest of honour is absent. Christian funerals – not celebrations of life or homegoings – ought to be different. They bring the limit-shattering experience of death into the realm of our life and language through biblically infused ritual and readings.

Forgetfulness, indeed, seems to mark the rites of passage as a whole. Babies are born, adolescents are launched, young people partner and the old die. But in our current cultural moment, there is no longer a shared sense of meaning assigned to these events by a common rite or institution.

Baptisms, confirmations, marriages and funerals continue to happen, though at a slow frequency that discourages all but the most courageous clergy. Now, however, they have competition.

And I’m not speaking of the competition that comes from a mosque down the street and a Hindu temple two blocks over. It’s rather competition that arises once enough people forget these meaning-assigning events are more than a product formed by consumer desire and available for purchase.

Perhaps weddings are the most obvious place to look at just how far-reaching the intertwining of rite as consumer product and self as consumer has become, but any clergy or funeral director will be able to signal how it is affecting their work too. I can remember when funeral homes self-segregated along denomination – Protestants took their dead to one, Catholics to another. There were no other options.

We need to reinvigorate a set of practices to help them make sense of what they’re going through.

My small town remains – in ways both delightful and frustrating – achingly slow in catching up to modernity. But like most funeral homes over the last half century, ours has moved from Protestant to nondenominational to multifaith. We are not at the stage yet where the chapel is renamed a celebration centre, clergy are replaced by religiously uncommitted celebrants, and the language of the funeral is completely eclipsed by the language of celebrations of life – and for that I am thankful.

But that day has come for many, especially in urban centres, and over time it will come to my town too.

This turn, astonishing in its rapidity, represents a fracturing of a close working relationship that was once taken for granted – that between the clergy and the funeral director. Funeral homes, because of the transformation wrought by consumerism, have had to make changes like those I mentioned earlier. Clergy, as a result, can no longer presume to have any sort of special relationship with their local director.

Every decision is now dictated by those making the arrangements. There may be a church funeral. There may be a chapel service. There may be a celebration of life at a local pub. There may be nothing at all. It is the funeral director’s task to co-ordinate the particulars in each instance so whatever happens provides solace to those who mourn.

Religion is now simply one among many options.

It is precisely this turn of events that means Christians need to start thinking again about the increasingly out-of-step ways in which they both die and care for their dead.

We are existentially afraid of death. The fear lurks deep in our bones.

Clergy and other Christian leaders can’t count any longer on the culture to teach our people how to die. We can’t rely on a special relationship with our local funeral director as we prepare a family for death or arrange a funeral. This is no fault of theirs. Clergy and churches are merely one consumer option among many in the designer funeral world.

So when we walk with a spouse, a child, a family, through the valley of the shadow of death we are going to need to recover and teach an old language, to reinvigorate a set of practices to help them make sense of what they’re going through.

So, just what does that language and these practices aim to announce?

First, death comes to us all. Prime minister, emperor, prince and pauper, we all will die. The hopes and fevered dreams of the transhumanists who want to upload consciousness into computers notwithstanding, the death rate for human beings remains constant at 100 per cent.

We are immersed in a culture that denies, distracts and distances itself from this uncomfortable fact – and the more it does so, the more death’s sheer inevitability terrifies us. If the Covid pandemic should have taught us anything, it is this – we are existentially afraid of death. The fear lurks deep in our bones. And when all the denial and distraction fails in the face of death’s awful presence, we are reduced nearly to nothing.

Second, death is an enemy. It is not a natural end to the process of life. However much this new mantra is repeated, Christians ought to know differently. I am convinced all humans intuit what Christian faith says explicitly. There is something deeply hostile to humanity in the encounter with death, even a so-called good one.

The Bible straightforwardly calls that hostility, that enmity, the wages of sin. The second death. The wrath of God. Death breaks every bond, shatters every friendship, reduces all our goals and dreams to nothing. Emptiness, emptiness, says the preacher, all is emptiness and chasing after the wind. Just so. "Did we in our own strength confide," wrote Martin Luther, "the battle would be losing…." And it is.

Third, death is defeated. Thankfully, Luther didn’t stop with the losing battle. Here’s how he continued. "… were not the right man on our side. The man of God’s own choosing. Dost ask who that may be? Christ Jesus it is He! Lord Sabaoth His name. From age to age the same. And He must win the battle."

Christian thinking about heaven ought to begin with union with Christ, the defeater of death.

The Christian funeral faces the inevitability and enmity of death squarely. But stoic resignation must finally give way to thanksgiving. For death in its awful might has been swallowed into the life and love of the Saviour who in His body on the cross took away our sins, bore the wrath of God and triumphed over sin, death and the devil.

When a Christian dies she does not fall into nothingness, but into the arms of the One who died for her. The One who, because He died and rose again, is Lord of both the living and the dead.

And that is the fourth proclamation of the Christian funeral – death can’t sunder the union with Christ He established. For all its fury, death could not sunder the union of humanity and deity that is the incarnate Lord. And death can’t sunder the union He has made with all who belong to Him.

For a long time my wife imagined heaven as a place of reunion with her mother, who died in her early 50s. Later, as a mother herself, heaven became the place where she would know and be known by her children forever.

Several years ago, while reading C. S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, a discomfiting question undid my wife’s thoughts. "Why is union with Jesus not heaven enough?" That is precisely where Christian thinking about heaven ought to begin – union with Christ, the defeater of death.

If there is to be any reunion with family and friends – and I pray there will be! – it is a reunion grounded in a greater Union, the Union of Head with Body, Vine with Branch, Christ at once God and Man who is in His divine humanity always with us and for us.

The Christian funeral is often dismissed these days – by believers! – as empty ritual. I’ve heard such dismissals myself. They couldn’t be more wrong. The Christian funeral remembers the dead and commends them to God. It brings the experience of death within the community of faith. It tells us the deep truth about ourselves, our sin and our salvation. It reminds us God and God alone is Life forever and that to live in Him is never finally to die.

Tim Perry is dean and professor of theology at Providence Theological Seminary, Otterburne, Man. His new book Funerals: For the Care of Souls is published by Lexham Press (www.LexhamPress.com). Illustrations for this Faith Today article are by Eva Bee.

FT CONVERSATIONS

We think our cover stories would be great to discuss with your small group or Bible study. Point members to www.FaithToday.ca/Funerals. Let us know how it goes (editor@FaithToday.ca).

- What do you think some of the biggest differences are between a funeral and a celebration of life?

- What has been the most memorable funeral you have attended?

- Tim Perry writes, "We are immersed in a culture that denies, distracts and distances itself from this uncomfortable fact and the more it does so, the more death’s sheer inevitability terrifies us." Do you agree with him? How can we counter this fear as church communities?

Listen to David Guretzki’s conversation with Tim Perry about funerals at www.FaithToday.ca/Podcasts.